How to keep your medical research relevant in an era of 'big science'

It seemed to me that consortium projects were becoming more prevalent. But I was concerned that I might be suffering from a cognitive bias.

It's like when you buy a new car at least in part because you have rarely seen one like it and then the minute you drive it out of the lot you see many of the same types of car. Such a is bias known as the availability heuristic.

My team and I did some quick research to make to see if we could find some evidence to support my perception that there are more and more consortium projects.

First, we looked on the webpage of the European Union's primary research consortia funding body, Horizon 2020. We searched under health and found 970 consortium projects as of the end of 2019. That does not include all medical research consortia as other subtopics have projects with a medical research theme, plus there are numerous national funding bodies and disease foundations that are supporting medical research consortia. It also does not include other regions of the world, such as North America. It is fair to say that there are probably something like 2 – 5 thousand medical research consortia.

If you do a simple search on Pub Med for articles that include the word 'consortium', you'll see that the use of word 'consortium' in publications doubled in the last five years.

The frequency of the use of the word consortium in PubMed citations is not the strongest evidence. However, it does support the notion that consortium projects are rapidly becoming commonplace.

What does this mean for you as a medical researcher?

The end of small science?

Large consortium projects such as the Human Genome Project fuel the concept that there is a distinction between 'big' and 'small' science. There is concern that ‘big science’ projects create a dominating constituency that block or limit ‘small science’ efforts (The End of "Small Science"? BY BRUCE ALBERTS SCIENCE28 SEP 2012: 1583).

A dominating constituency has indeed contributed to the spectacular failure of the efforts to develop new treatments for Alzheimer's. Those who did not include the amyloid hypothesis in their work were shut out from funding and blocked in their efforts to publish. And now it seems that we need alternatives to the amyloid hypothesis to make progess.

If you are not part of a dominating constituency, there is a real risk that 'big science' smothers your 'small science'. How do you prevent that from happening?

The obvious answer is to build or join a consortium project, but it is not so simple.

The right kind of consortium project

Just being in a consortium is no guarantee.

Consortium projects are complex and complicated structures that can be very slow-moving. The funding you get as a partner might be nice, but the attendant bureaucracy and communication challenges may ultimately be more of a hindrance than a benefit.

Suffice it to say; it is not as simple as raising your hand to indicate you want to be in a consortium. There is much more to it.

It is frustrating to see leading researchers struggle to build a consortium that in the end, achieves nothing more than adding more bureaucracy to the research process. This is, however, a predictable result. As a medical researcher, you know what you know.

Medical research unfolds in a specific manner. Successful researchers optimise the scientific method. They also know that working in a small group is an excellent way to make progress.

Even the most successful medical researchers get involved in at most a handful of consortium projects throughout their career. It is therefore understandable that most apply a 'small science' approach to running a consortium project.

It is, ironically, a 'small science' mindset that leads to overburdensome and underperforming consortium projects.

The superpower of consortia

The superpower of consortia is the opportunity to access the collective expertise and experience of a broad array of different disciplines and stakeholders. A consortium is, in a sense, a human neural network.

When consortium partners interact frequently, and in a structured manner, the consortium as a whole can solve difficult problems and achieve a high level of creativity.

Even highly successful researchers who are leaders in their field tell me that being involved in a highly interactive consortium project doubled their research productivity.

Pharmaceutical companies with research budgets that dwarf many major researcher institutions recognise this reality. There are many bottlenecks and barriers to innovation that despite large budgets, they cannot solve on their own.

These benefits only accrue when you have a high degree of interaction where partners are working closely together to solve problems.

It is a compounding effect.

A high degree of interaction leads to both faster problem solving and more rapid identification of new opportunities. Such a level of broad interaction runs counter to the 'small science' mindset.

Untapped potential

The untapped potential of consortium projects is my motivation for writing this post. I want to do more than just convince you to consider getting involved in a consortium project.

What follows is a set of steps you can take to build a consortium and begin the process of insulating your outstanding 'small science' from being overshadowed by a ‘big science’ constituency.

The best consortium projects combine both big and small science.

The thing is that you do not have to wait for others to offer partnership in a consortium project. You can be proactive and form a consortium now. Here is how.

Step one: Map out your consortium project strategy.

It is easy and even fun to informally think about strategy. However, it only becomes real once you write it down. A strategy that exists only in your head is a dream. Your move to double your research output through consortium projects begins with being concrete about your strategy.

How do you start?

You begin by being selfish. To be more precise, start by thinking about your needs.

Raymond Maslow is famous for his hierarchy of needs (Maslow's pyramid). The concept is that you first have to take care of your more foundational needs before you can move on to more significant and more fulfilling aspirational needs. At the top of Maslow’s pyramid is about meaningful work, what Maslow called self-actualisation.

I have crafted a researcher's needs pyramid. You position yourself better to decide what you want to get out of a given consortium project by taking the time to think through the different levels of the pyramid. If you do not have a specific consortium project, just think of an ideal consortium project. You can use the worksheet posted below to sketch out your strategy. I recommend that once you fill in each of the blocks, you consolidate the wording and keep a version of the pyramid close at hand and review it every time you think about or take part in a consortium activity.

Begin at the top. What is a paradigm shift or a big difference you would like to happen in your field? If it is something that will have a direct impact on the lives of individuals suffering from disease even better. Don't get hung up on this step. Do have some fun and think about the change you would like to see even if it seems out of reach.

Download a researcher's needs pyramid worksheet

The next step down is prestige. Prestige can mean many different things, but you can think about it as leadership. What types of leadership roles would you like to have in a consortium project? Is it the Coordinator of the whole project? Leader of a work package, or a clinical study? Maybe you could lead the effort to develop a standard? There are plenty of leadership roles in consortium projects.

Then comes publications. It is often said that publications are the currency of science. I disagree. The currency is the techniques and assets that you have, which are part of the foundation of the pyramid.

Think about at least three high impact publications you envision will be produced in a consortium project.

When you visualise something concretely, it is much more likely to happen. So, get to as much detail as possible.

Yes, of course, you need to know results before you know what a paper will be about. You can anticipate at least in a broad sense what papers are possible, can't you?

Next is data. You need data to write those publications. Thinking about what data you will need is crucial to the design of a consortium project that will fulfil your needs. Since you have filled in the papers you want to write, thinking about what data you will need should be easy.

Your currency as a researcher is your techniques and assays. These are what you trade to build up collaborations. You should be clear about what techniques or assays you can bring to a consortium project. More importantly, think about how you can further develop and improve your techniques and assets.

Consortium projects are about making a real difference, but they are also about development. A subgoal is always building the innovation capacity of the partners.

What would be the next step for developing one of your core and most novel techniques?

Last is funding. While you may have been primarily interested in consortium projects because of the funding they bring, funding is just an immediate benefit.

The upper part of the pyramid speaks to the multitude of other benefits. Think about how much funding you will have to ask for to achieve the ambitions you have listed out above.

Once you have the pyramid filled in, use it. Communicate all aspects of your pyramid when you are developing the project. If you have done this exercise for an ongoing consortium project, then take every opportunity you can to discuss your needs with your partners. You don't need to reveal your pyramid literally. It is your strategy. But being open about what you want is essential to making consortium projects work.

Step two: Get a group of collaborators together and brainstorm the most important problems in your field

Brainstorming on important problems might seem incredibly obvious. You know what the problems are in your field and so do your collaborators. But does everyone see precisely the same problem? Probably not.

By having a dialogue about the problems your field faces, you will undoubtedly learn about interesting differences in what others think is most important. By putting this dialogue into a structure where you map out not only problems but also their causes and effects, you will be in an excellent position to define and impactful solution to the main problems by designing a project that addresses the root causes of a set of problems.

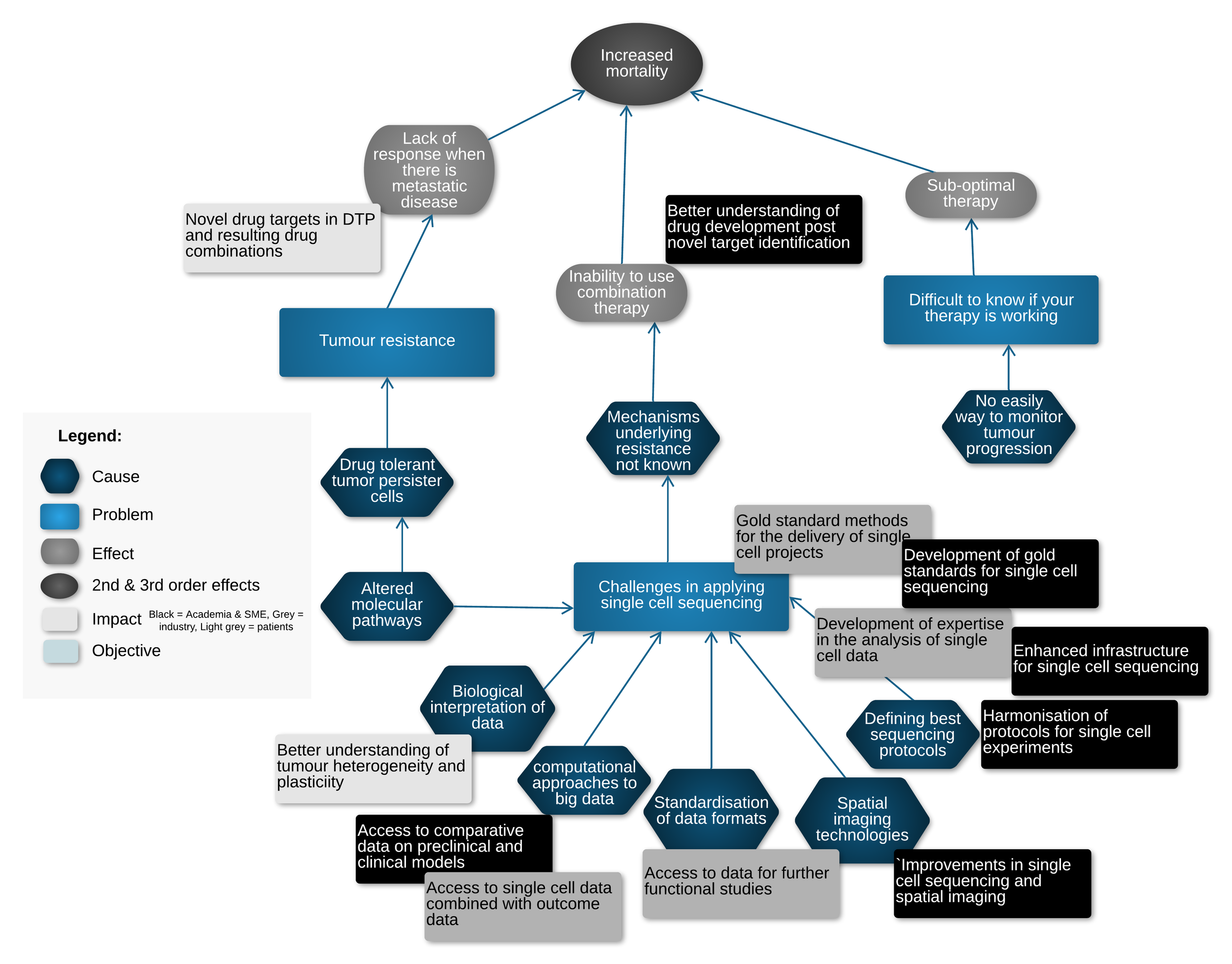

Example Problem-objective-Impact map summarizing the Innovative Medicines Initiative's (IMI) call topic on tumour plasticity

Mind-mapping the problems, causes and effects in this way makes it easy to identify relationships between problems and to think about areas of overlap.

Step three: Consider what causes are best addressed by a consortium project.

Consortium projects are best suited for achieving things that are not easily achievable on your own. You could argue that most of medical research falls into that category. While it is true that all medical research can benefit from the interactions you have in a highly interactive consortium project, some achievements can only be addressed by working together. Take, for example, agreeing upon and developing a standard set of preclinical models for a particular area of research. You will need to have a critical mass of different groups agreeing to your models if they are going to have an impact. Another challenge for which consortium projects are well suited is pulling together existing datasets. Such an activity requires agreement on a common data model and then input from experts who know the individual datasets well. One of my favourite consortium activities is determining how to make medical research more patient-centred. This at a minimal requires the meaningful engagement of patient stakeholders. Here is an extended but not comprehensive list:

Common preclinical models

Integrating existing datasets

Making research more patient-centric

Developing and gaining acceptance for new biomarkers

Coordinating efforts to achieve a significant goal, i.e. sequencing the human genome

Generating momentum for a new direction – new therapy for cystic fibrosis, a vaccine for asthma

Shifting a paradigm of disease understanding – multi-omic profiling to define new disease subpopulations

Application of new technologies that will have a disruptive impact on the whole healthcare system – eHealth, Artificial intelligence.

Pulling resources to address an urgent medical need, i.e. Ebola crisis, or develop therapies in the domain that faces return on investment challenges such as new antibiotics

Let me know in the comments below if you can think of other areas of focus, and I will add them to the list.

Put a star on your problem/cause/effect map or list out some ideas of what causes need a consortium approach. It is essential to think about this upfront because it provides the rationale for forming and getting funding for a consortium. It does not mean that a consortium will not deliver on other aspects. It is having clarity on the 'Why a consortium' aspects that helps to get others engaged. It is the first step toward developing a compelling, shared vision.

Step four: Decide upon what impact you want to have

When I first started to work as a project designer, we often left any consideration of impact until the very end. It was an afterthought. Of course, everyone had some notion of the impact in the back of their minds, but it was not explicitly stated or considered.

The impact is another way of saying what will be different. The easiest way to think about impact is to adopt the perspective of a stakeholder. What will that stakeholder be able to do, or how will a particular type of stakeholder's life be better after the project is delivered?

For example, integrating several existing datasets will mean that a researcher can validate findings or conduct research at scale. A better sub-classification of a disease will mean that it will be easier for a clinician to tailor treatment and deliver truly precise management. A more patient-centred approach to research will mean that new therapies address problems patients care about. It won't be just about treating a meaningless number.

A bit later in the process, you will go into more detail on a stakeholder by stakeholder analysis. For now, think in general terms and write down impacts that you and your group can think of. I typically add this as a grey box to the effect side of the problem, cause, effect map.

Step five: Have an initial go at the objectives.

If you know what impact you want to have, you can begin to think about your objectives. Project plan elements are often like layers of the same concept with expanded detail the more profound and deeper you go. Refine the project plan elements iteratively. At this point draft a set of objectives. Keep in mind that objectives should be both aspirational and inspirational. The way to do that is to add a 'so what' statement on the end of the objective.

"We are going to identify new biomarkers for disease 'x' so that new biologic treatments with a narrow therapeutic index will only be given to those individuals who are most likely to benefit."

It does not have to be precisely 'so that'. It looks redundant if you end each objective with 'so that'. Use the end of the objective to describe the impact you intend to have.

Step six: Have a dialogue on what the ideal project would look like

Once you have mapped out the problems, causes and effects, and you have considered why you need a consortium you are ready to work with your core group of collaborators to begin to think about what the ideal project should be. Begin with the ideal. The point is to define what you need to do clearly. Later you will have to shape the project in many different ways to fit the funding or the vagaries of a particular call topic or demands of a commercial funding partner. For now, embrace the freedom to contemplate the ideal.

Finding unexpected connections is one of the most satisfying aspects of designing consortium projects. Often such connections result in a synergy that makes the overall project more feasible. Using mind mapping tool to depict project activities that enables you to drag different activities to different positions makes it easier to identify and represent connections or relatedness a powerful way. It is also helping those you are working with to think more laterally and stimulates them to consider what they can bring to the concept of the project. It this regards it is also helpful for one person to have an initial start on generating the map of the project.

At BioSci Consulting, we use an online tool called Lucid Chart. It is a multi-functional tool that allows you not only to draw a mind map; it is also has a templating function that makes it easy to put the who concept into a 'project canvas'. For the same reasons that you should represent the dialogue in a mind map, a canvas has the same effect for mapping the concept of the project in one connected graphic.

As you can see, the canvas includes some elements of the problem/cause/effect map as well. Transfer those elements to the canvas prior to coming to the session where you have the dialogue on 'what' you will do in the project.

Download a consortium project design canvas

Step seven: List out the key results

Key results are a variation of the more concrete objectives. Think deliverables. The phrase "key results" is used because a result does not have to be a 'deliverable' per se. Deliverables should be something tangible. Whatever the case, it is essential to be as explicit as possible. This is the first iteration of your deliverables, so it is high level and meant to help move the dialogue forward with your collaborators. It is much easier for them to look at your initial list and see what is missing.

Step eight: Fill in the needs and impact assessment

Now that you have started to get more detail into your project, you can take the process of defining the impact your project will have a bit further. As mentioned before you should think of impact from the perspectives of different types of stakeholders. To do that first consider what various stakeholders need concerning the problem(s) you are aiming to solve. Clinicians need better ways to predict which patients will respond to which therapeutic interventions.

Once you identify a need, describe the consortium's response to that need. For the clinician looking to improve response prediction, this would be identifying new biomarkers or stratification approaches. Write a short declarative one-sentence statement. Then describe the impact in regards to this specific need. Remember that impact is 'what will be different'. It might be what you wrote before, but you will now likely be able to refine your wording and be more specific.

The last line of the needs and impact assessment is success metrics. The way to think of success metrics is as something quantifiable that indicates you have been successful in achieving your intended impact. Keeping to our previous example, it could be identifying two new biomarkers. Try to include a quantity. By doing so, you are starting the process of thinking about the scope of your project. If your success metric was ten validated biomarkers that would not be feasible in most cases.

There is a box to the right of the individual lines. This box is where you list out different stakeholders who have the need you describe and will experience the impact. I usually list out 3-4 different stakeholder types. It can be difficult because some impacts will affect every kind of stakeholder. List the top four types of stakeholders based upon who will be the most directly impacted. It should be just a rough idea. There are only four needs, impact assessment boxes on the canvas. You can list out more, but to help to facilitate the dialogue with your collaborators chose the top four. One way to decide is to have one box where each of the four most crucial stakeholder type is at the top of the list.

Step nine: Fill in the 'why only we can do this.'

Look over what you have filled in so far and consider why the group you have assembled is the group that has to do this project. If you find that this is difficult to answer, then you need new partners. Often things like participation in preceding projects, or being the leaders in a particular field are good reasons. This is a point where it is a good idea to consider if you have engaged patient stakeholder organisations. For many diseases, there are only a few major patient stakeholder organisations. If you can involve them in a meaningful way, it will be a significant differentiator for your consortium project.

If you have identified partners, you need this is the time to reach out to them to gauge their interest, if you know who they are. It may be that you want to mine the thoughts and ideas of your collaborators.

Step ten: Take a stab at the visionary concept

Now the fun begins. An exciting visionary concept is a powerful motivator and a fantastic communication tool. In the U-BIOPRED project, we have the visionary idea of creating a 'handprint' of severe asthma to improve patient stratification. A visionary concept makes it easy to explain the project to people. It has also served to motivate partners to do more when the project has been particularly challenging.

To begin a visionary concept, think about an analogy. A project that was integrating and cataloguing datasets might have the visionary concept of being the 'google of datasets'. You might end up with an entirely different visionary concept, but this will stimulate the dialogue with your collaborators.

Step eleven: Conduct a dialogue around the completed canvas

Send your draft completed canvas to your collaborators and plan a new dialogue session. I always make the point that this is just a draft based upon the previous dialogue and meant to help stimulate ideas. Then have the dialogue and step through the canvas box by box. If you have had enough dialogue about the problems, the what and the objectives you can quickly move through these. Present your ideas about each section and listen for the response. Actively solicit input and expand the dialogue by asking questions. Be open to completely changing the whole concept. Ask about feasibility and scope. Will other partners be needed? Are there commercial organisations that would be interested in your project?

Step twelve: Scan for grant funding opportunities

By no means limit your search for funding of your project to grant funding, but an open call topic is a great way to solidify your ideas. It helps you consolidate your focus and adds a sense of urgency to your efforts.

EU level

On a more regional or national level look to traditional funding routes but also consider grants to support small businesses and innovation. Projects funded by those types of grants are the perfect setting to develop and make use of a consortium mindset. Those that run and build a successful company have a different perspective than an academic researcher. There is a lot of potential value gain for all those involved when you can effectively integrate those perspectives.

When you are scanning for opportunities, be open-minded. Committees write grant call topic texts. Call topic texts consist of densely written prose that presents several ideas and concepts. This is why, when designing a project, I read and re-read the call text. The point is that what may not seem like a suitable call can be or at least it fits one aspect of your ideal project. Doing the work in the preceding steps helps in this regard. The more detail you have, the more likely you will be to find a match to a call topic text.

If there is a call topic text you think is suitable, then move to build a consortium and design a project that fits that call topic. One thing not to forget is to check the timeline. One month is not realistic for developing a consortium project. You may be able to write the required text but getting the right partners and incorporating their perspective won't happen in a month. Even two to three months is not enough. Don't think you are missing out. Take a long view and build a consortium and the concept for a project that is solid. You can gain a lot of the benefits of working in a consortium just by brainstorming with other partners. Regardless of the presence of a suitable call topic or not move forward to the next step.

Step thirteen: engage different stakeholders

When you engage different types of stakeholders, you set the foundation for a long-term consortium. It may be that those different stakeholders fund aspects of the project themselves, or they may help in identifying other funding sources. Disease foundations, for example, can be very useful in motivating companies, grant funding agencies, insurance companies, and even governments to create opportunities for funding. Some even fund a significant amount of research themselves. The same is true for companies.

Engage other stakeholders with an open mind. You should be inviting them to co-create or co-develop the project with you. Gone are the days when funding is based upon reputation alone. Projects need to deliver on organisations' objectives and not just the bigger picture. You will have a more robust project from the effort. The canvas is often a good starting point, but for internal decision making, there will need to be more concrete and specific detail. It is also wise to clearly state the value the project will deliver.

Step fourteen: Adopt a highly interactive consortium mindset

A consortium project can be just a slightly different way of working, another way of packaging funding. Or, it can be a radically different way of working that changes everything. The difference lies with you and your partners. When you buy into the concept of working in consortia, you unleash significant potential. Even if you are a highly productive researcher who is a leader in your field, a consortium project can double your research productivity. The gain is not only in publications, it is also about making a real difference. What does it take to 'buy-in'?

You have to commit to having a highly interactive consortium. Consortia are potential quagmires because there are so many different organisations and so many different disciplines and stakeholders who don't understand each other. But that is also their strength. The cognitive diversity present in any consortium project can be leveraged to achieve unexpected levels of creativity and to solve problems in a highly efficient manner.

There are five principles you can apply to make any consortium highly interactive.

Engage stakeholders

Fulfil partners needs while delivering on broader objectives

Leverage multi-disciplinary thinking

Work in iterative cycles

Foster opportunities to do more

These principles comprise what I call the highly interactive consortium mindset. I have pulled together my experience and combined it with concepts from a broad array of other disciplines to illustrate how to apply these principles in a book Assembled Chaos: Advancing your medical career while changing the future of medicine through highly interactive consortia. The book is full of anecdotes, examples and more concrete guidance. Click here if you would like to get two chapters of the book for free.

Once you have completed the preceding thirteen steps, you are well on your way to establishing a consortium. It is then time to be sure that the consortium you are building reaches its full potential. If the project you are developing is just a bunch of silos dressed up to look like a consortium, you are merely adding a layer of complexity and bureaucracy you don't need.

Conclusion

These fourteen steps should make it clearer how you can start to build a highly interactive consortium that will deliver paradigm-shifting projects. There is no reason to wait. You can begin this process tomorrow.

I believe that that consortium science is itself a new paradigm for the conduct of medical research and innovation that is the near and present future. Staying relevant in the era of 'big science' is up to you.

If you need some additional help in figuring out how to get started and what to do, shoot me an email scottwagers@biosciconsulting.com and I will let you know how we work with clients. There may even be an opportunity for you to join one of the consortia we are supporting.